A new blow has been dealt to European farmers hoping to use advanced agricultural technology, a decision that could have implications for farmers here in Canada.

A European high court has ruled new gene editing technology, initially designed for plants, will be dealt with in the same regulatory manner as the transgenic technology that consumers in North America have come to accept, but Europe despises.

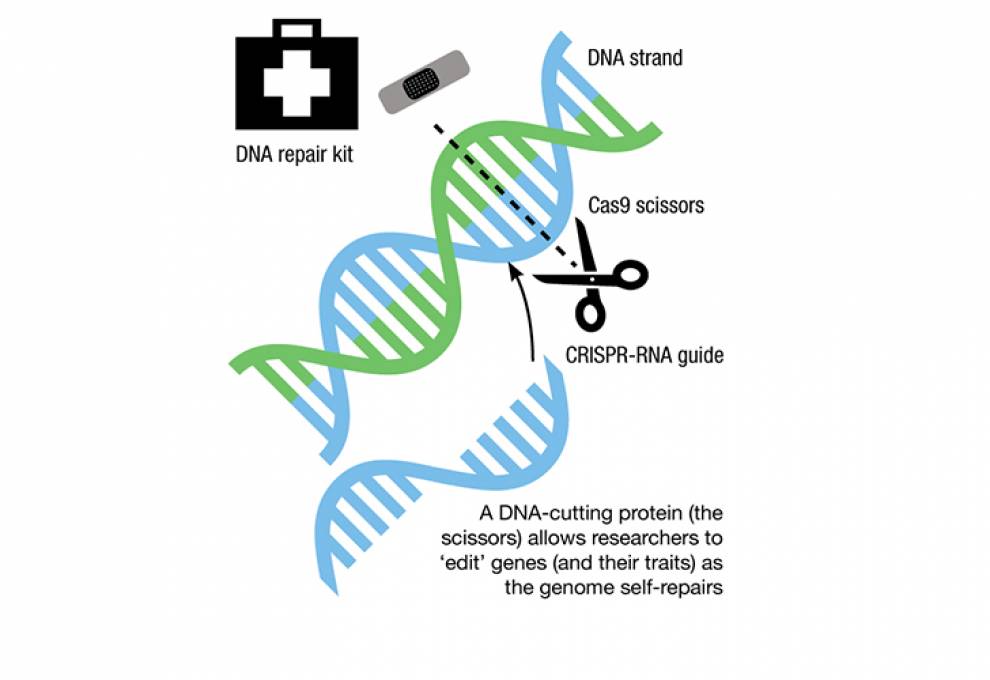

That’s huge. Many scientists say gene editing – sometimes called by the acronym CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspersed Short Palindromic Repeats) -- is much different.

Here’s why.

Gene editing involves disabling, removing or inserting genes that are responsible for specific traits, related to the likes of taste, appearance, and performance, among others. With advances in scientists’ understanding of genetic make-up, identifying certain genes’ roles and manipulating them is easier than ever.

Transgenic technology, on the other hand, involves transferring genes from one species into another, that would not occur in nature. In the plant world, the textbook case here is Monsanto’s Roundup-Ready soybeans. They contained a gene that made them tolerate the herbicide glyphosate (trade name Roundup), also made by Monsanto. It effectively killed weeds, but not the glyphosate-tolerant soybeans growing beside them in the same field.

The science community hoped regulators worldwide would take a softer line against gene-edited organisms. And indeed, the United States did so earlier this summer, which is not surprising, given how North America has pioneered

genetically modified crops.

But in late July, the European court ruled that crops created using gene editing would be subject to the same stringent testing as genetically modified crops. It’s estimated such testing costs around $35 million per crop. That means only the biggest companies will be able to afford it, and that only crops with the highest returns will be involved.

The story is much different here. Elsewhere in The Grower (pg 13), you’ll read that J.R. Simplot Company, one of North America’s largest potato, avocado and strawberry processors, has announced it’s pursuing gene-editing technology.

It says such technology could reduce potato bruising and browning, and cut some of the 3.6 billion pounds of potato food waste annually. Other advantages it cites are higher yields on less land, meaning fewer pesticides, water and labour.

And it has support from the United Potato Growers of Canada.

“I’ve followed their research very closely,” says the organization’s general manager Kevin MacIsaac. “The science is there; it’s now more about getting the acceptance in the consuming public and the retail chains to recognize that.”

Agriculture is trying to get out in front of this so gene editing doesn’t get lambasted like transgenics did when they were introduced a few decades ago.

To that end, the Coalition for Responsible Gene Editing in Agriculture, which has varied stakeholder interests (mainly industry), is developing a framework that it says will “provide assurance to the food system and other stakeholders that those using gene editing within the framework are doing so responsibly.”

The public strokes its beard about all genetic modification, but more so in Europe, where the hangover from genetic experiments in World War II with humans still remains, and more so yet with transgenics.

Europeans think technology is fine in many arenas, and have developed superb products as a result, such as automobiles. Ironically, some of the companies that champion new technology in agriculture are based in Europe, or have a strong presence there.

Progressive thinkers in the European ag sector know technology makes a difference to producers. They know how yields have grown thanks to breeding technology. They know how traits such as disease resistance have led to greater profitability.

For Canadian farmers, the bottom line is that they’ll have technology available to them that Europeans don’t – again. Whether consumers accept it and trust it will depend greatly on how the industry rolls it out.

Add new comment